Chip in Now to Stand Up for Working People

Working people need a voice more than ever and Working America is making that happen.

Working people need a voice more than ever and Working America is making that happen.

07/05/2016

OVERVIEW

Over the past six months, Working America has studied how Donald Trump’s rhetoric has affected working-class communities across America. As part of our ongoing effort to counter the hard-right agenda he espouses, we wanted to gain a sense of how Latino voters are perceiving his candidacy in swing-state Florida.

Over a seven-day span in early June, we held 509 face-to-face conversations with likely Latino voters across eight working-class precincts in the Orlando area. Of the people we spoke with, 97 percent self-identified as Latino or Hispanic. Within that group, 68 percent said they were Puerto Rican, followed by a segment of voters originally from Colombia, Ecuador, Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Mexico. One in four interactions with voters took place in Spanish.

As in previous endeavors in Ohio and Pennsylvania, Working America focused on likely voters with household incomes below $75,000. Our goal was to explore the issues that were on voters’ minds and the presidential candidates they were considering. In this community, we also asked about the direct impact that Trump’s candidacy was having on their lives. We found that fear of a Trump presidency is motivating the majority of Latino citizens we talked with to vote in November. Many also reported a heightened level of threat and discrimination stemming from the anti-immigrant vitriol unleashed by the rise of right-wing rhetoric. While our method differed from traditional public opinion polling and the sample was not representative, our findings suggest a population ripe for authentic engagement and mobilization to advance a progressive agenda.

KEY FINDINGS

A majority of Latino voters said Trump made them more likely to vote.

On May 26, Trump officially clinched enough delegates to earn the GOP nomination; our Orlando canvass began a week later. Of the people we spoke with, 82 percent said they were very likely to vote in November. A majority expressed that they were motivated by his bid for the presidency, with 55 percent saying they were more likely to vote because of his candidacy. Of the 64 people who voted in 2008 but did not vote in the 2012 presidential election, nearly three-quarters said they are very likely to vote in this election and just over half selected a Democratic candidate. Overall, 63 percent of voters we spoke with said they were supporting a Democrat for president, 3 percent picked Trump and 31 percent were undecided.

Trump appears to be alienating Latino Republican and independent voters.

Latino voters who supported Trump gave reasons that were remarkably similar to those of white working-class voters. His 16 supporters (3 percent of the 509 people with whom we spoke) liked that he “speaks his mind” and felt we need a president who has a strong business acumen. One woman felt his language wasn’t divisive, arguing, “he speaks the truth and the American people can’t handle the truth.”

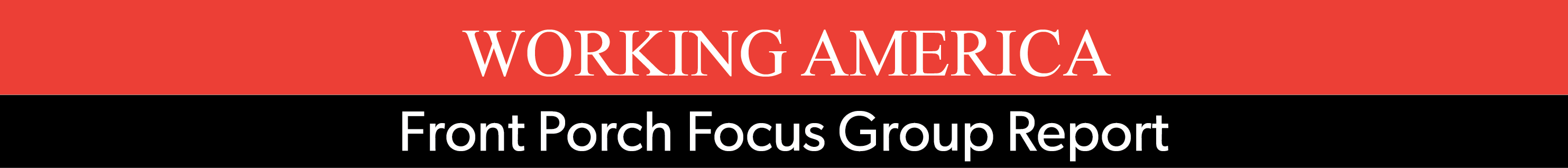

While our sample was small and not representative, there are signs of fraying support for Trump even within his own party. Among the 66 registered Republicans we spoke with, we did not see strong support for Trump. In fact, one in three registered Republicans said they were supporting a Democrat and 42 percent were still undecided. Several of these voters said they chose Clinton because Trump doesn’t sound like a Republican leader.

Across all party lines, many voters were still up for grabs. Of the 284 registered Democrats we spoke with, one in four were undecided. 42 percent of Republicans remained undecided, and one in three voters with no party affiliation fell in that camp as well.

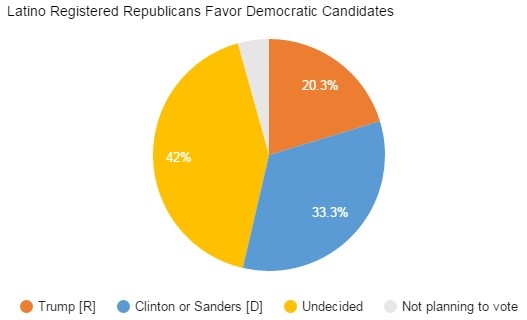

On the question of whether Trump speaks for the GOP or embodies conservative values, Orlando Latinos do not view Trump as a messenger for the Republican Party: 90 percent say he only speaks for himself and not the GOP. As the chart on the right shows, three in four voters viewed him as an outlier altogether.

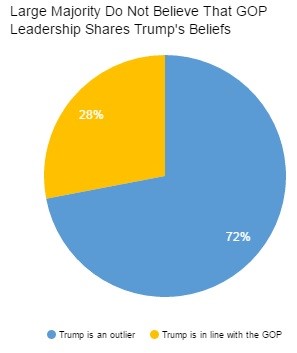

Nearly one in five Latino voters in Orlando said they have personally experienced or observed bigoted language and racist incidents during Trump’s candidacy.

The Orlando voters we spoke with were eloquent about the impact of Trump’s race-baiting bigotry on their lives and sense of security. Nearly 80 percent of Orlando Latinos strongly felt that he’s used extreme language, legitimized hate speech and inflamed the public.

For 19 percent of Orlando Latinos, Trump’s bigoted rhetoric is seeping into their daily lives in the form of increased discrimination. Several voters said they receive more mean looks from strangers. They especially felt that when they speak Spanish in public they receive stares.

At the office. A bilingual Puerto Rican woman was told by upper management she spoke “horrible English” and was forbidden from speaking Spanish on the job, which represented a shift in policy. She said until recently speaking Spanish had not been a problem on the job.

At the gas station. A Puerto Rican woman was helping a fellow Floridian translate what a customer wanted from a worker behind the counter. The gas station employee said: “If you can’t speak English, don’t speak anything at all.” Under his breath, he said he couldn’t wait until Trump builds the wall. The woman responded: “I’m from Puerto Rico. A wall isn’t going to make me not be here. I have the right to speak Spanish.”

At the skating rink. While a canvasser was speaking with a woman at her door, her husband joined the conversation to say that discrimination has definitely increased since Trump began his campaign. He described what it was like to pick up their daughter from the local skating rink. There were some people wearing Trump masks who were screaming in his face. He said it made him feel very unwelcome.

At the mall. A 59-year-old Puerto Rican woman was shopping when she saw another Latino woman tending to her crying child. A white woman approached the mother and told her “You should take that baby back to your country so he can cry there.”

At the dollar store. A 49-year-old Puerto Rican said she was shopping at Family Dollar, and the manager was rude to her. He asked: “What are you? Where are you from? You speak Spanish, you must be something.” She’s seen other people in her community face discrimination at a church group, where white women said to Latinos: “Go back to Mexico. Trump is gonna get all of you out.”

These types of incidents left over half of the Latino voters we spoke with “likely” or “very likely” to get out and speak with their neighbors about the election. One Colombian woman expressed, “At the end of the day, all Latinos are one.”

But others were afraid and viewed the presence of Trump supporters as a reason to stay away and disengage from discussion. Within some households and communities, politics was viewed as a source of tension and friction, not a way to start conversations or influence opinions. One Bernie Sanders supporter pointed out neighbors across the street who had set up a cross with a Trump yard sign on it. She expressed that this type of political expression made her fearful and wary of the consequences of discussing politics in public.

It’s still the economy first.

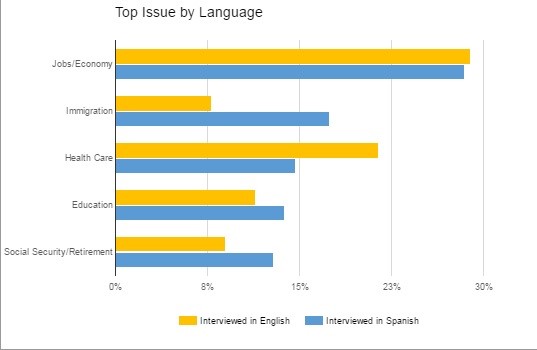

As with white working-class voters, good jobs and the economy was the top issue for the Latino voters we canvassed. Nearly three in 10 cited jobs and the economy. This trend was consistent among both English and Spanish speakers. (Just over a quarter of our 509 conversations were conducted in Spanish.) Voters volunteered concerns about low wages and the lack of job opportunities.

Views on immigration varied depending on language and citizenship.

For English speakers, immigration ranked fifth (8 percent) among top concerns for Orlando Latinos. But for Spanish speakers, the issue rose to second (17 percent). Our canvassers noted anecdotally that voters held mixed views on immigration. Some Puerto Ricans were sympathetic to other Latinos’ struggles, but since they are already citizens, some were less sympathetic to immigrants from other countries and less open to a path to citizenship. One Puerto Rican woman said that she didn’t support Trump but agreed that people who come to the U.S. illegally should be deported.

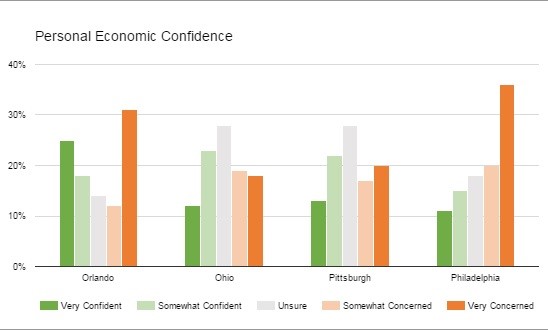

Latino voters in Orlando were divided in their views of their personal economic future and the economic fate of their communities.

Across the U.S., Working America canvassers ask voters how they feel about their own economic future as well as that of their community. A larger proportion of working-class voters (25 percent) in Orlando felt very confident about their personal circumstances than did voters in Ohio, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. However, over 30 percent also reported being “very concerned about their personal economic situation.” This level of concern is higher than anywhere else but Philadelphia. We also found Spanish speakers were more confident than English speakers.

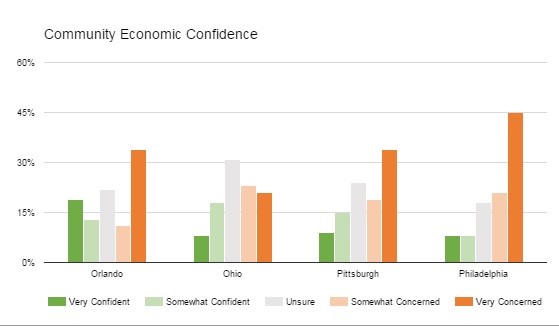

At the community level, nearly one in five Orlando Latino voters felt “very confident” about the future of their community’s economy – again, much higher than in Ohio, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, where less than 10 percent of voters felt the same way. But twice as many were “very concerned” about the economic health of their community. The difference was even larger between the white and black communities we canvassed in Ohio and Pennsylvania, where black voters were much more concerned.

METHODOLOGY

Unlike traditional public opinion polling, which is based on randomly sampled people intended to be representative of a given population, we targeted likely Latino voters in eight targeted precincts across Orange County, Florida. Of the 509 people we spoke with, 5 percent were Working America members and 95 percent were members of the general public.

The canvassed populations skewed female over male (58 percent to 42 percent) and older (43 percent were over 60 years old). We employed statistical modeling and party registration history to ensure that we reached a mix of Republicans (14 percent), Democrats (56 percent) and independents (31 percent).

Conversations ranged from a few minutes to as long as 15 minutes. Canvassers sought to gauge what sparked voters’ feelings on key issues and candidate choices. We did not try to move voters to an alternative candidate and did not persuade them to support one candidate over another. Individuals we canvassed could choose not to answer a specific question, which resulted in slightly different totals for each response.

We use cookies and other tracking technologies on our website. Examples of uses are to enable to improve your browsing experience on our website and show you content that is relevant to you.