Chip in Now to Stand Up for Working People

Working people need a voice more than ever and Working America is making that happen.

Working people need a voice more than ever and Working America is making that happen.

06/19/2020

The COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic crisis have both disproportionately affected people of color, particularly black communities. A key component of the federal response to the economic disruption was an expansion of unemployment benefits under the CARES Act. Historically, there is a well-documented pattern of people eligible for unemployment benefits not applying for those benefits, but this pattern is even more pronounced among black workers.

For this project, Working America is leveraging its digital organizing capacity and clinical testing know-how to boost UI utilization rates among black workers. We wanted to understand the UI utilization problem, use our available toolset to help mitigate harm and decrease the risk of an even deeper economic recession, and ultimately get more eligible workers to boost their household incomes.

In order to understand why people don’t utilize unemployment benefits, Working America began outreach to affected communities to document their experiences with the unemployment system, their attitudes toward the system, and knowledge of the application process. Why do some black workers choose not to apply for unemployment benefits? What can be done to reverse this pattern?

The first phase of our project is to hear from affected communities about the experience with the UI program, understand their attitudes and awareness of the process, and answer the question: Why do black workers apply or not apply and ultimately receive or not receive this important benefit? The findings from the first phase will inform the next steps of testing approaches to increase application and receipt of benefits. The ultimate goal is to develop and test effective methods of increasing income and applying clinical rigor to measure the outcomes.

Working America’s digital canvassing program (targeted text messages, email and phone calls reaching 3 million people a week) has already shown substantial success reaching large numbers of workers, educating them about the risk of COVID-19 and convincing them to change social behavior. In follow-up phone conversations, we have heard the extent to which these workers are affected — 35% of people told us that they or someone in their households had lost a job as a result of the pandemic. In response, Working America organizers followed up with a wave of text message outreach that identified 100,000 workers interested in accessing UI benefits.

Directly Affected Workers are Hard to Reach/Many Skeptical about Conversations

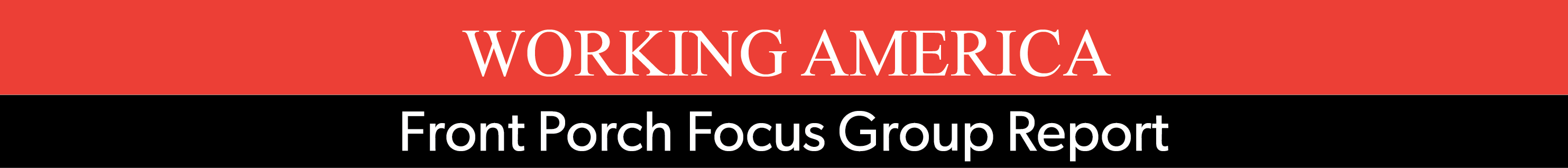

One notable finding is that only a fraction of the people we spoke with were directly affected by job or income loss due to the COVID-19 economic crisis. More frequently, those willing to open up about their experiences were speaking on behalf of a family member or close friend.

Additionally, our organizers encountered skepticism about the reason for our call. With increased buzz about scammers taking advantage of people during the pandemic, some people we reached wanted to end the call quickly and were suspicious about having a conversation. We were able to overcome these objections by talking about Working America’s track record of fighting for working people and our local work in the state.

Why people don’t apply for benefits

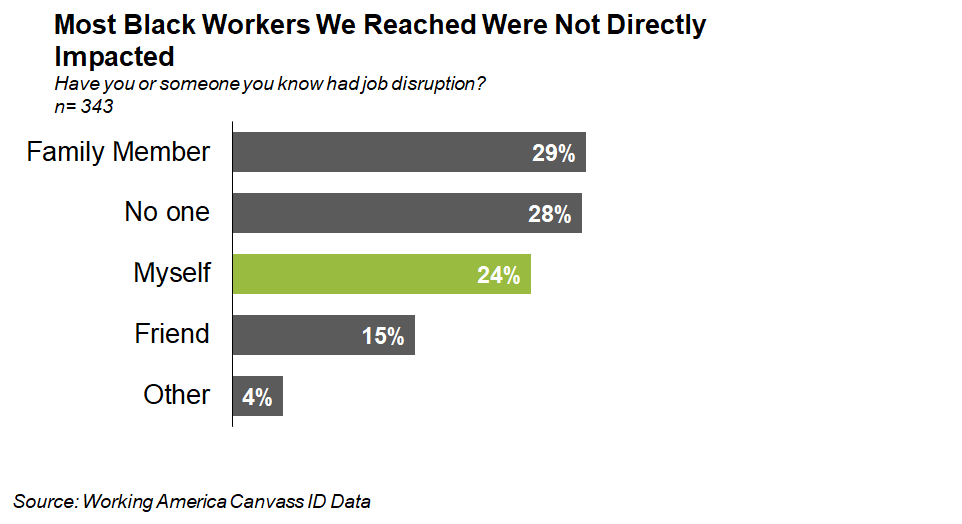

The most common explanations offered for not applying for benefits include a lack of awareness about eligibility, particularly when it came to the new federal benefits. Canvassers spoke with a number of people who had their hours reduced rather than being laid off; in many cases these workers were unaware they were eligible for unemployment benefits.

Those who didn’t apply also cited difficulties with the application process.

Ayana, a 46-year-old Westland, Michigan, resident working in health care, said, “My friends, neighbors and family members all have had to apply to UI … They all had technical difficulties [when applying]. It seemed like no one could ever talk to a live person.”

Keshia, a 44-year-old Greensboro, North Carolina, resident who works in human resources, said, “My sister lost her job in the medical field. She had to wake up very, very early, like 3 a.m., in order to apply through the online portal. Otherwise, it would be so slow it wouldn’t work. She was denied because there was some discrepancy with her name, and had to keep going back and forth, but she eventually got it.”

Even those who had internet access and found the initial online application relatively seamless nevertheless struggled through red tape and a lack of responsiveness during the rest of the process.

Beverly, a 52-year-old Detroit resident working in catering, said, “It just don’t make sense to me why I can’t seem to get a hold of anybody to help. The last check I got was early April. I’m just trying to get by.”

Jimmie, a 41-year-old Greensboro, North Carolina, resident, said his girlfriend was laid off, applied for unemployment benefits on May 10, but more than a month later has yet to receive any money.

Tecara, a 35-year-old Greensboro, North Carolina, resident working as a corporate trainer, said she was furloughed in mid-April, but as of mid-June has still not received any benefits, despite the fact that her employer helped her through the application process.

Most workers are not aware of new federal benefits and the expanded eligibility requirements. As a result, many who are eligible have not applied.

Many workers are uncertain about unemployment benefits due to the circumstances of their work. The assortment of employment relationships present friction with changing rules of eligibility for unemployment insurance. Many workers do not know if and how their situations relate to eligibility — gig economy workers losing customers due to COVID-19, people working two jobs and losing one, seeing a reduction in hours and many more. Even after applying, far too many workers face long wait times (8+ weeks) before receiving their benefits. This delay muddies whether they need to continue to file weekly claim reports while waiting to receive benefits. Without clear and consistent information, workers do not know if they are eligible or what to do while they wait.

Regional differences in information about application process

Workers in Michigan seemed more informed about the process than those in North Carolina. This may be attributable to the fact that auto industry workers and employers had experience navigating the unemployment system during the Great Recession. Some automotive industry workers described employers facilitating the unemployment benefit application process, which also seems to be a factor in participation in the program.

Angela, a 48-year-old Ecorse, Michigan, resident working in the automotive industry, said she wasn’t laid off or furloughed, but had coworkers and friends who were due to the pandemic. Regarding the unemployment application process, she said, “My friends that work for the autos were taken care of, they didn’t have a problem.”

Tamara, a 45-year-old Bloomfield, Michigan, resident, said her husband was laid off from his job at Chrysler, but said that his employer facilitated the unemployment application process.

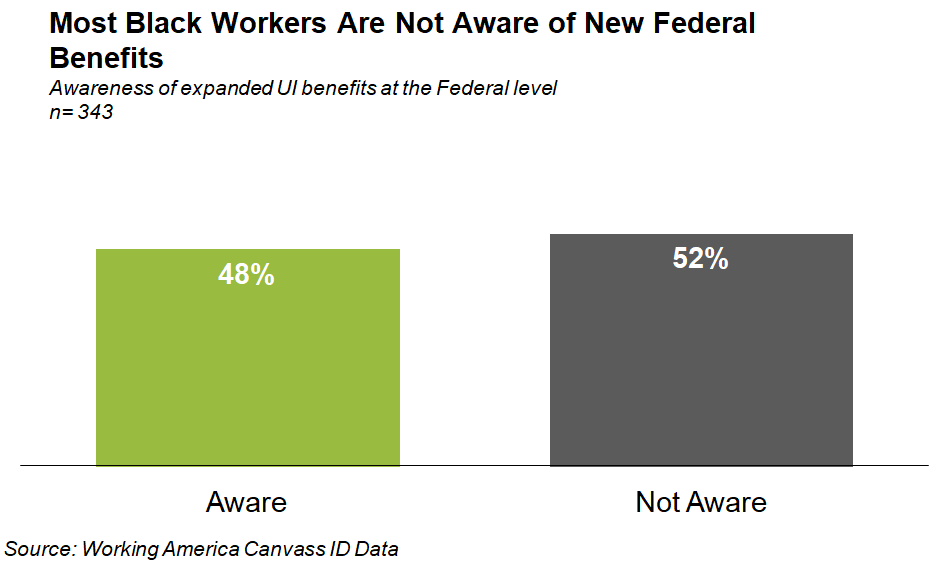

Willingness to help others navigate the unemployment application process

When we asked workers if they were willing to help others navigate the unemployment application process, more than 2 out of 3 responded that they were willing to help. Many cited their own difficulties with the process in explaining their willingness to help others.

Ronton, a 49-year-old High Point, Michigan, resident, said, “I absolutely would. If everyone was helping each other things would be a lot better.”

Ayana, a 46-year-old Westland, Michigan resident, said, “I would help anyone [apply for benefits], because it’s not going to get any better.”

Angela, a 48-year-old Ecorse, Michigan, resident, said, “I can self-navigate because I had to do it before, so I can help people.”

Conclusion

The first phase of this project has yielded valuable insights, but our work continues. We are taking these lessons and conducting a clinical experiment aimed at increasing awareness of information on unemployment benefits among those directly and indirectly affected. By measuring the likelihood of applying for unemployment benefits, we hope to apply the learning from our clinical experiment to scale up effective practices and ultimately make a concrete impact on rates of benefit application among black workers.

We use cookies and other tracking technologies on our website. Examples of uses are to enable to improve your browsing experience on our website and show you content that is relevant to you.