Chip in Now to Stand Up for Working People

Working people need a voice more than ever and Working America is making that happen.

Working people need a voice more than ever and Working America is making that happen.

05/06/2021

The problem

Historically, many eligible workers are deprived of access to earned Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefits. This deprivation is particularly acute for Black workers, who also are concentrated in lower-wage job sectors, have fewer saved assets, and are among the most likely to be displaced in economic downturns as was the case during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

What We’re Doing/What We’ve Done

Early in the pandemic, we partnered with policy experts at the National Employment Law Project (NELP), with the support of Open Society Foundations, to address the unemployment crisis — organizing aimed at improving utilization of unemployment benefits by Black workers who have been disproportionately denied what’s due them. Law, policy and practice may be the culprit, but the solution begins with mobilization. What we’ve seen in our work is encouraging for broader organizing for equity across issues.

We used large-scale organizing capacity, existing relationships with over 1 million Black workers and experience using rigorous clinical measurement informed program to address the long-standing problem of eligible Black workers not accessing UI. Our goal was to identify the pathway to building relationships with potential members and activists to scale the spread of information regarding UI. We ultimately wanted to increase the number of eligible Black workers claiming UI benefits, thus bringing much needed resources to the community. This work is built upon learning developed across multiple phases to engage Black workers in Pennsylvania, Michigan and North Carolina, Ohio, Georgia, Wisconsin. In later phases, the work was exclusively conducted in Pennsylvania.

Summary of findings

*Peer Mobilizers are workers who were contacted via a phone conversation and agreed to engage their personal networks regarding Unemployment Insurance.

Program Design

Econometrics Research and Experiment Implementation

WAEF is well practiced in conducting and evaluating randomized control tests of various aspects of its program, but this tool is mostly applied to areas of civic participation. To properly design and evaluate the impact of our organizing efforts, the research design needed to overcome a number of complicating factors.

Partnership with Columbia Labor Lab: First Administrative Level Experiment

To better understand and design a robust experiment, WAEF partnered with the Columbia University Labor Lab. Researchers from the Columbia University Labor Lab collaborated with WAEF to study the impact of the organizing program on the UI claims rate in targeted counties as part of a clinical experiment. The key finding is that for every 1 peer mobilizer phone conversation with a worker held during the experimental period, an additional 3.18 people claimed UI benefits. Based on US Department of Labor data for the post-treatment period, the average UI beneficiary received $318 in weekly benefits for 15.3 weeks. The cost to generate a single conversation with a worker was $163, and 748 conversations were held during this period.

Researchers crafted a dual design experiment. In Group 1, 72 counties in Georgia, North Carolina Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin were randomly assigned to a control or a treatment condition, blocked into comparable pairs, and indexed for a series of economic indicators (share Black, median wage, unemployment rate in preceding months, Labor force). WAEF contacted Black workers in 36 of those counties, reaching 2.4% of the counties’ population via SMS and 0.01% by follow-up phone call. The observed increase in UI claims of 0.03pp (SE=0.09, p= 0.74, 95% CI -0.14, 0.20) reflected positive but not a statistically-significant increase in claims. When these results are rescaled to reflect increase in applications per contact, we see that for every one phone conversation, 3.2 additional UI claims were filed. (Note: The lack of statistical significance is unsurprising given the narrow share of the population contacted in the experimental counties.)

Encouragingly, when examining the counties where the Black workers made up a large share of the overall population (and therefore a larger share of the population was contacted as part of the program), we identified even larger increases in UI claims, suggesting that the contact was driving the outcome. In counties where greater than 20% of the population is Black, WAEF contacted 10.8% of the population via SMS and 0.05% via peer mobilizer calls. The observed increase in UI claims is 0.17pp (SE= 0.15, p= 0.25, 95% CI -0.12, 0.47). While still not meeting conventional standards of statistical significance, the increased statistical precision and treatment effect estimates, compared to the overall population in counties where a larger share of the population was treated, is consistent with the conclusion that the program drove increased claims. The rescaled representation of these results show that for every one phone conversation 3.77 additional UI claims were filed.

Validation in Pennsylvania: Second Administrative Level Experiment

With positive indications from the first experiment, WAEF conducted a validation randomized control trial and difference in difference measurement in Pennsylvania and Philadelphia respectively. Pennsylvania allowed for more robust validation as the state publishes the race of the UI applicants at the county level. This phase of the project also included communication with Latinx/Hispanic workers in the state.

The key finding from this validation study is that WAEF has likely developed a model to successfully engage black workers (increasing UI applications both statewide and in Philadelphia). For every peer mobilizer we estimate the program generates ~3.1 applications statewide and ~1.7 applications in Philadelphia. Moreover, this study finds that while Latinx/Hispanic workers are responsive and seek out information the model of engagement was not as consistently successful. (The program was roughly 4 times more effective at mobilizing Black workers to reach out to their peers).

Utilizing learning and advice from the Columbia Labor Lab– Researchers at WAEF crafted a dual design experiment. Study 1, randomized 64 counties in Pennsylvania to a control or a treatment condition, blocked into comparable pairs, and indexed for economic indicators. WAEF contacted Black and Latinx/Hispanic workers. Study 2, compares Philadelphia to the control counties in the state in a non-randomized difference and difference measurement.

As shown in the chart below, across multiple mobilization and administrative measures WAEF had considerable success mobilizing Black workers. In particular, the positive indications from the Columbia Labor Lab Experiment are consistent with these findings–this model increases UI applicants within the Black community.

On the other hand, the evidence suggests on both peer mobilization and administrative measurements this model was not as successful with Latinx/Hispanic communities. Given the WAEF team spent nearly a year engaging the black community this result is not surprising. More operational focus and testing are needed to refine a model catered to serving the Latinx/Hispanic community.

| Summary Statistics | |||||||

| Study | Race/ Ethnicity | Diff | P-value | Peer Mobilizers | Applications Generated | Applications Generated Per Mobilizer | Share of Pop. Peer Mobilized |

| PA Counties Randomization | Black | 0.48% | 0.13 | 283 | 884 | 3.1 | 0.15% |

| PA Counties Randomization | Latinx/Hispanic | -0.26% | 0.93 | 48 | n/a | n/a | 0.03% |

| Philly vs. Control Counties | Black | 0.58% | 0.04 | 1,290 | 2,153 | 1.7 | 0.35% |

| Philly vs. Control Counties | Latinx/Hispanic | 0.19% | 0.37 | 91 | 164 | 1.8 | 0.11% |

Our Practices:

Peer Mobilizer analysis :

Over the course of the program we engaged over 22,000 respondents and developed almost 10,270 “peer mobilizers”. These are folks that signaled in some way that they were interested in helping their community recover from the economic crisis. Our most effective and most scalable mode of contact was through SMS peer-to-peer messaging and so our “peer mobilzers” primary mode of communication is via text messaging. Second to SMS was phone, both virtual phone banks (VPB) and ThruTalk which produced over 14,000 conversations.

An analysis of these folks reveals that:

All of these stats are important when you think about the typical profile of an activist- generally a high propensity voter, who is educated and has a higher income. In our peer mobilization model we have found a way to engage and activate Black, middle aged workers and women who are middle-low income, and previously unengaged in voting.

| Demographics of the Peer Mobilizers (PA) | |

| Age (Mean) | 54 |

| Age: Under 25 | 6% |

| Age: 25 to 39 | 22% |

| AgeL 40 to 49 | 16% |

| Age: 50 to 64 | 33% |

| Age: 65+ | 23% |

| Voted in 2020 | 78% |

| Mean Household Income | $39,738 |

| Share Non-College | 88% |

| Category | PA | MI | NC | Totals |

| All Respondents | 31,715 | 3,080 | 5,089 | 39,884 |

| Text Repliers | 19,322 | 3,080 | 5,089 | 27,491 |

| VPB Convos | 6,074 | 547 | 776 | 7,397 |

| ThruTalk Convos | 2,873 | N/A | N/A | 2,873 |

| Total Peer Mobilizers | 9,947 | 547 | 776 | 10,270 |

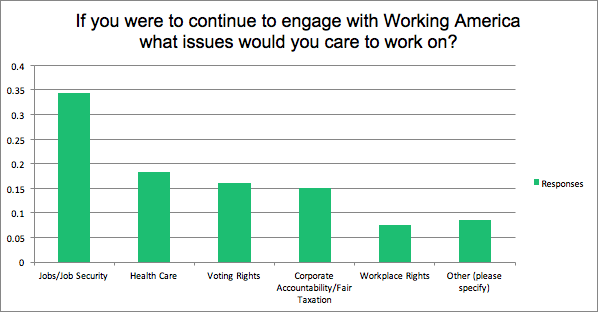

Given what we’ve learned about these individuals over the course of this experiment, we have built a ladder of engagement to keep them actively engaged on this and other related issues. Our primary mode of communication is SMS and phones as explained earlier but we know that this group is comfortable with taking small actions that involve informing their community about issues that impact them. We would ultimately like to see our “peer mobilizers” take the tools and information that we provide for them and set up in their own communities to organize and disseminate information they see best but we have to move them from an initial text message to action. For more details on the ladder of engagement click here.

Socialization

Our goal was to build out the relationship we had with the peer mobilzers. One element of that was to find an easy on ramp to our program. The on ramp was achieved by creating a simple task that could be asked and completed via SMS and phones. “Will you help our community recover by sharing this UI Guide?” Once the peer mobiloizer indicated a willingness to complete this action they were then subsequently communicated with via phone, email, text and Facebook ads reminding them of their commitment to share the info and how easily accessible the information was. Early in the process, workers were brought together in community with UI experts to answer questions they had about the application process, this both helped validate Working America as a useful resource and allowed attendees to to feel a sense of community with others who were experiencing the same thing. We consistently kept our peer mobilzers and broader pool of SMS responders engaged with updates at the state and federal level re: UI as well as worked to meet their most immediate needs sharing information about food banks, rental assistance and other basics.

Organizer Engagement

Building on our large-scale contact via SMS and phones we also had an organizer directly engaging with peer mobilizers to build momentum and deepen relationships. These conversations (enumerated below) gave us insight into the peer mobilization experience and provided us with anecdotes of the experiences of those both directly and indirectly impacted by unemployment. These conversations were often follow ups to our phone bank conversations lasting 45-minutes to an hour and designed to really get folks to share their experiences and talk about their networks.

| Category | PA | MI | NC | Totals |

| Organizer Convos | 519 | 44 | 123 | 686 |

| Anecdotes | 116 | 5 | 17 | 138 |

Relationships have long been understood as the foundation of grassroots organizing praxis. As portrayed in Marge Piercy’s poem The Low Road:

“Alone, you can fight . . . but they roll over you. Two people can keep each other sane, can give support, conviction . . . Three people are a delegation, a committee, a wedge . . . A dozen make a demonstration. A hundred fill a hall. A thousand you have solidarity and your own newsletter”.

Over the course of the BUI campaign, we tested new ways of connecting people while we were unable to utilize our traditional methods of mobilizing the communities we organize. In place of talking to people on their doorsteps, we utilized a multi-channel digital communication stream through which we made multiple touches via SMS, email, phone, and social media. Through these channels, we asked people to apply for benefits, urge the Senate to pass more economic relief, and to be peer mobilizers by sharing reliable information and encouraging people in their communities to take the same actions.

Peer Mobilizer Observations

Our quantitative data shows that the peer mobilizer model works– we saw 3.1 applications for every peer mobilizer we activated. Here is what we heard from tose peer mobilizers:

Another success of our program was the inspiring mobilization we saw when we asked people to share a call-to-action urging Congress to pass extensions to the federal unemployment programs and reinstate the supplemental benefits:

In addition to the initial mobilizing of their networks, the peer mobilizers expressed a willingness to continue to check in and support those they reached out to. When our organizer followed up with people who had committed to sharing the guide and asked if the guide had helped anyone they shared it with, those who hadn’t already checked-in committed to do so, often without direct prompting from the organizer. Some of the peer mobilizers formed sustained support networks with their friends, family, and/or community in which they continued to help each other navigate through the often-confusing and fast changing landscape of the pandemic-era unemployment system.

Impact of the Pandemic

The pandemic perculded building an in-person community with these peer mobilers and virtual efforts to build that community we ultimately not successful long term

The multiple touches made through our digital capacities may have been helpful in familiarizing the people we contacted with unemployment insurance prior to organizing conversations, but it took extra effort to get the same impact that a face-to-face conversation would. Our staff capacity and digital assets on their own would not spread the information as broadly as we needed. Hence, the peer mobilizer model we developed and incorporated in the ladder of engagement was critical to bringing this project to scale because it implemented the relational strategies we know to be our strongest weapon.

Interaction with our Program

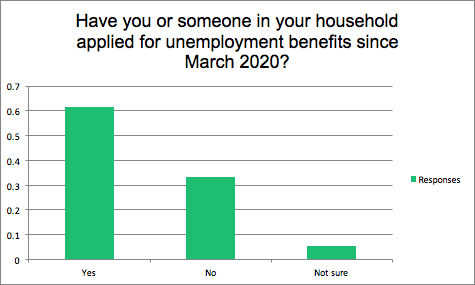

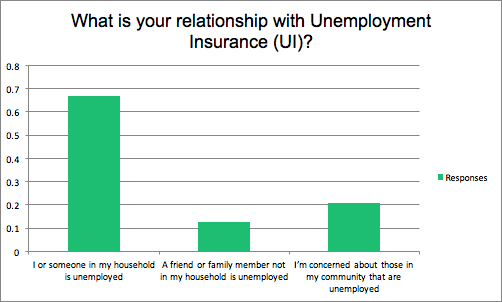

During the BUI experiment, we distributed two surveys to help us learn more about the peer mobilizers–one in December 2020 and the other in May 2021. The purpose of these surveys was to gain quantitative data to supplement the anecdotal data gained from organizer conversations, to inform how we will continue to engage the peer mobilizers, and to understand how peer mobilizers were interacting with our program. The December 2020 survey was sent to 9,421 emails and had 168 respondents and the May 2021 survey was sent to 1480 emails and texted to 8,185 numbers and had 139 respondents.

Communications with our most engaged mobilizers

The survey data reveals the value of our program was successful at engaging a group of folks who either were directly impacted themselves or who had relationships with others who lost jobs. Furthermore, we directly addressed the second most commonly reported barrier to getting benefits which was a lack of knowledge on how to apply.

Partner Engagement

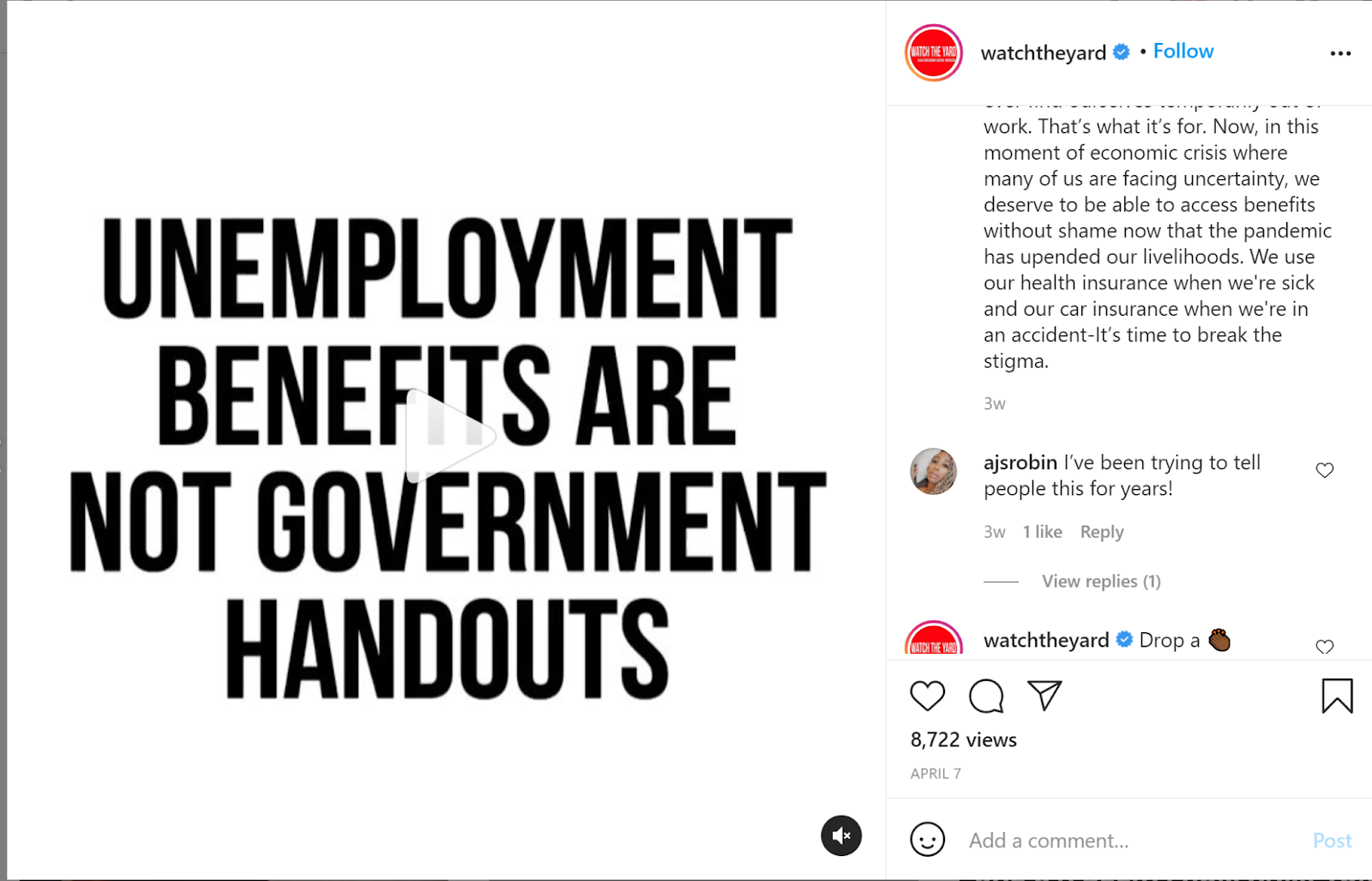

While Working America is a trusted messenger with our membership, the target audience for outreach extended well beyond our membership base. In order to facilitate better communication with Black workers we reached out to community partners to help spread the information we curated on Unemployment Insurance. While we had national partners like Push Black and NELP, we found it essential to partner with local and state based organizations that were in and of the communities that we organized. Local labor, community and faith based organizations and direct service providers were the primary groups we directed our outreach efforts to with varying levels of success. We recognize that there are Black Digital networks, like PushBlack and Watch the Yard that hold a unique space for conversations like these- communicating in spaces where Black workers are comfortable having these conversations and collecting information.

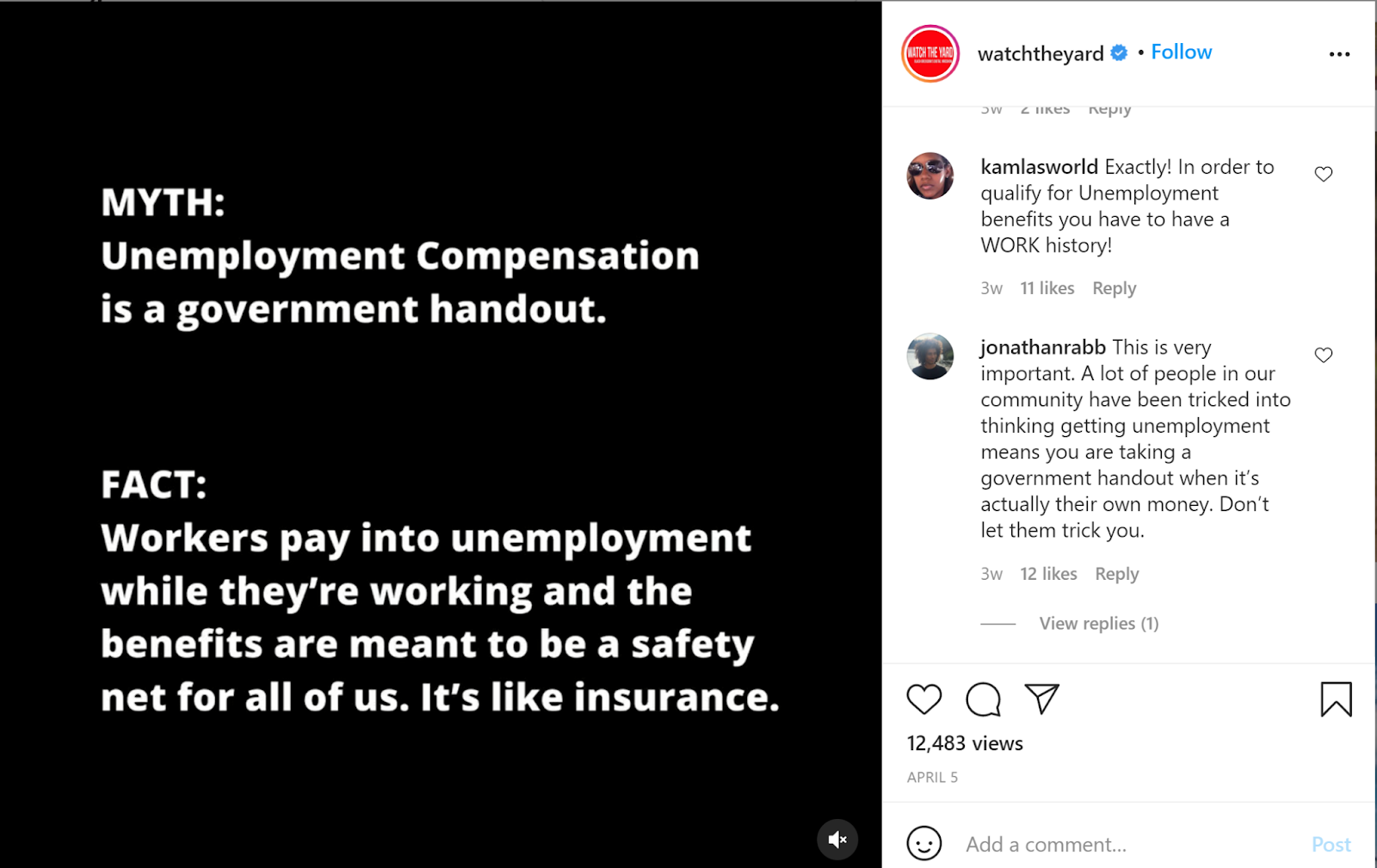

Digital Partnership- Watch The Yard (WTY)

Working America partnered with Watch the Yard, a digital media platform that produces content for members of Black fraternities and sororities. The goal in this partnership was to leverage WTY’s existing audience and network with the information that the BUI campaign provided, we wanted to destigmatize Unemployment Insurance and encourage those who saw the information to either sign up or share the information with those in their networks who needed it. Because of some of the natural barriers of this project- cold calling/texting, asking about employment status, asking someone to share the info we felt that leveraging this warmed audience through a platform and a messenger that they were already familiar with was a path worth utilizing. We found this particularly useful in conversation around de-stigmatizing the utilization of earned benefits like Unemployment, see a sample of screenshots below.

The program:

WTY Screen Shots (full)

Learning Partnership with PushBlack (assets)

In our partnership with PushBlack we shared our learnings on effective messaging from digital and SMS that they then incorporated into their digital messaging program. Messages like the ones below were used in both of our programs.

They found that leading with an unsettling statistic is the better way to solicit attention and engagement than simply posing a question to Black PA users and we would suggest taking this approach in the future.

Michigan Workers Rights Table

Led by Michigan United, this workers rights table included multiple partners located throughout Michigan including the Michigan AFL-CIO state fed, the Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP), ROC United, Prosperity Michigan, Detroit Action, the University of Michigan Workers’ Rights Clinic, IASTE Local 26, United for Respect, SEIU Local 1, Michigan People’s Campaign, The Impact Project, and Laborers’ Local 1191.

Their priorities are focused on holding the UI agency and Attorney General’s office accountable to their responsibility to support and protect Michigan workers and to build a coalition that can win pro-worker UI reforms in the state of Michigan. More info on their legislative agenda can be found here.

We partnered with them by signing onto their UI reform campaign, and we asked them to support our UI webinar by sharing out the promotional materials to their audiences.

Pennsylvania Workers Support Network

This workers table was recently started by the Unemployment Compensation Unit at Philadelphia Legal Assistance. Partners on this table include Pennsylvania Legal Aid, Legal Aid of Southern Pennsylvania (LASP), VietLead, Pennsylvania Health Access Network (PHAN), Mid-Atlantic LiUNA, Philadelphia Unemployment Project, Ceiba Philadelphia, Community Legal Services of Philadelphia, SEAMAAC, Unite Here, Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC).

This work group was called to support the launch of a new statewide resource for Pennsylvania workers applying for or on unemployment. Plans to create a statewide website to provide accessible legal information to workers has been in the works for a couple years, and it’s launch was pushed up due to the pandemic and the rollout of a new, modernized Pennsylvania unemployment system. UCHelp.org went live on June 2, 2021, shortly before the launch of the new UC system. Members of this workgroup, including Working America, supported it’s launch by sharing it out to communities we serve and organize in. Continued plans for this workgroup include translating the information into multiple languages and incorporating resources from partners (i.e. PHAN) to make UCHelp.org a one-stop-shop for Pennsylvania workers.

AFL-CIO UI Task Force

This national coalition is led by Cecilie Counts from the AFL-CIO. The task force includes AFSCME, American Federation of Teachers, The United Association of Journeymen and Apprentices of the Plumbing and Pipefitting Industry, IASTE, National Education Association, Sheet Metal Air Rail Transportation (SMART) Union, USW, IAMAW, UFCW, International Union of Painters and Allied Trades (IUPAT), Actors’ Equity Association, and the AFL-CIO Department for Professional Employees.

This task was started in response to Republican-led states abruptly ending the federal UI benefits. This group exists to be a voice for workers on this issue as the voices of a few business owners have influenced legislators to cut off a lifeline that workers in many industries were counting on. Currently, this group has been meeting with advisors of the House Finance Committee and Senate Ways and Means to discuss whether or not federal UI reforms are possible and what work needs to be done to pass reforms through the Senate.

Outreach Takeaways:

Challenges with progressing the program

When we first started to focus our program on Philadelphia, our hope was that we would be able to further reduce the barriers to applying by either identifying or creating a way for potential applicants to receive one-on-one support. However, while we did identify legal partners our organizer could refer people to under specific circumstances, we were unable to find organizations in the Philadelphia metro who could provide the scale of support needed given that service providers who were already strained during the pandemic.

We briefly discussed the idea of training our peer mobilizers to walk others through the application process but concluded it would carry too many legal risks. Barriers were: 1)Unemployment Insurance deals with people’s personal and financial information 2) and there are many individual situations that can complicate the application process driving concerns that encouraging our contacts to walk others through the application process could result in harm to the displaced workers we were seeking to help. A mistake on the application could result in denial of benefits or delays to benefits that could take months to resolve. 3), without a system to vet activists, we feared that running such a program could result in especially vulnerable workers (i.e. immigrants and refugees, people lacking computer literacy, and low-wage workers with nontraditional work histories) being victimized by identity theft and fraud.

Throughout the program, our organizer struggled to move activists who expressed interest in taking action up the ladder of engagement as we continued to figure out how to define roles to plug them into. Early attempts to deepen engagement–for example, virtual community action team meetings–proved to be unsustainable when considering the capacity of our team. With one organizer balancing various components of the campaign, research, the management of outreach, recruiting of speakers/storytellers, and prep work required for these meetings to run smoothly and be of value proved to be beyond our capacity.

As we explore future engagement with peer mobilizers, we should develop a ladder of engagement and delineate roles prior to or very early on in our engagement with our audience. By having clear goals, strategy, and roles for activists to take on, we will have stronger campaign infrastructure that will allow us to build and sustain a base early on. What we have observed is, given the right issue–urgent with immediate real-life impacts, we are able to identify, engage and activate a peer mobilizer model that has the potential to empower working people in communities across the country.

We use cookies and other tracking technologies on our website. Examples of uses are to enable to improve your browsing experience on our website and show you content that is relevant to you.